by Pat Conaty and David Bollier

“The power of open source principles, now proven beyond a doubt, is rapidly proliferating into many other areas of culture, production and social life. The prospect of more participatory, socially convivial forms of production – accountable to communities and mindful of the larger common good – has never seemed more achievable. Still, there are important organizational, legal and financial hurdles to overcome – not to mention cultural and political differences – that must be dealt with if co-operatives are to find common ground with digital commoners and peer producers. Fortunately, there are emerging models such as multi-stakeholder cooperatives that could be vehicles for such cooperation.”

See this paper in the Commons Transition Wiki

Download as a PDF

Download as EPUB (zip)

INTRODUCTION

For people who participate in commons, peer production or co-operatives, the emerging economy presents a frustrating paradox in the enormous mismatch between cooperative culture on the one hand and the organizational forms, on the other hand, that can sustain it and advance the general well-being of society.

New forms of peer production are creating common pools of knowledge, code and design and entirely new socio-economic-technical sectors of production and governance. This sprawling, eclectic realm based on free software, open knowledge, open design and open hardware relies upon social collaboration and sharing, and aspires to become a sector of self-sustaining and autonomous commons.

Unfortunately, because its economic forms are generally embedded in capitalist economies – dependent on closed intellectual property, venture capital funding, for-profit corporate structures, and so forth – the new “open models” are generally subordinated to hyper-competitive markets with capitalist dynamics. Notwithstanding brash claims for the liberating potential of the “sharing economy,” peer production on open platforms may simply replace the more classic forms of proprietary capitalism with a commons/corporate hybrid that commandeers various commons to serve the interests of capital.

Meanwhile, the co-operative movement in many parts of the world faces its own challenges in coming to terms with contemporary technologies and the political economy. A number of large co-operatives now resemble global corporations in their market behaviors, organizational cultures and management styles. If they are not fending off threats of privatization, their managers and policies function at a distance from co-op members, who often no longer participate actively or take part in a shared culture. As for smaller co-ops, many have been shunted to the margins of both the market and society by larger dominant forces. Thus without creative solutions they are unable to compete in large, concentrated markets or embrace networking technologies that might enhance their co-operative powers.

For these and other reasons, the co-operative movement, despite its illustrious history and impressive organizational and financial models, no longer inspires the popular social imagination or has the élan and dramatic impact that it did in, say, the 1890s, 1920s or 1970s. The power of global capital and markets, digital technologies and consumerist culture has operated perversely in ways that have reined in the ambitions of some parts of the co-operative movement. In recent years, however, there has been a renewed sense of purpose and confidence across the international co-operative sector. The United Nations declared 2012 “International Year of Co-operatives,” and in the same year, a rejuvenated International Co-operative Alliance adopted an ambitious blueprint for a “co-operative decade” intended to establish the business and ecological leadership of the co-operative model, in which ownership rests with those most closely involved in the business. There is also a growing receptivity to the idea of open co-operativism, as seen in Robin Murray’s book, Co-operation in the Age of Google – a theme that echoes the cardinal first principle of the co-operative movement, “open and inclusive membership.”

These are welcome developments because a decline of co-operatives diminishes the general welfare of society. The general public increasingly has few alternatives to large, predatory corporations whose anti-social behaviors are often sanctioned by captive legislators and state bureaucracies. While the “social economy” is gaining ground in many parts of the world and some commercial sectors, its benefits are often killed in the cradle or kept within strict limits. The market/state duopoly, a partnership that divides responsibility for production and governance while pushing an agenda of relentless economic growth and neoliberal policies, continues largely unchecked.

All of this prompts the question: Is it possible to imagine a new sort of synthesis or synergy between the emerging peer production and commons movement on the one hand, and growing, innovative elements of the co-operative and solidarity economy movements on the other? Both share a deep commitment to social cooperation as a constructive social and economic force. Yet both draw upon very different histories, cultures, identities and aspirations in formulating their visions of the future. There is both great promise in the two movements growing more closely together, but also significant barriers to that occurring.

EXPLORING THE POSSIBILITIES OF AN OPEN CO-OPERATIVISM

To explore the possibilities, the Commons Strategies Group organized and convened a workshop of a dozen notable activists, policy experts, academics and project leaders in Berlin, Germany, on August 27-28, 2014. (A list of participants is included as Appendix A.) The meetings, “Toward an Open Co-operativism,” were supported by the Heinrich Böll Foundation, with assistance from the Charles Léopold Mayer Foundation of France. A core question of the workshop was: How can social cooperation in contemporary life be structured to better serve the interests of the co-operators/commoners and society in general, in a techno/political economy that currently insists upon appropriating surplus value for private capital?

Commoners tend to approach this question from a different perspective, history and focus than many in the co-operative movement. That’s because commoners tend to occupy a space outside of markets, for example, while co-operatives are generally market entities themselves. Commoners tend to have few institutional resources or revenue streams, but instead rely upon powerful networks of collaboration based on open platforms.

By contrast, co-operatives today constitute a substantial segment of modern economies. There are more than 1 billion co-op members in 2.6 million co-operatives around the world, and they generate an estimated US$2.98 trillion in annual revenue. If this economy were a united country, it would be the fifth largest economy in the world, after Germany.[2] Yet the transformative impact of this economic power is less than its size would suggest. Where there is a strong co-operative presence, such as local banking in Germany, housing in Sweden or farming in India, co-ops can change market outcomes. But where they are a minority competitor, unless they are innovators, many co-ops have simply adapted to the competitive practices and ethic of the capitalist economy and politics, rather than struggling to re-invent “co-operative commonwealth” models for our time. Their influence in national political life is no longer as progressive and innovative as it once was, nor as focused on improving the lot of ordinary citizens. There are many reasons: the scale of older co-operative enterprises, the distance between managers and beneficiary-members, the backward-looking terms of existing legislation for co-ops, and the cultural affinities between “new co-ops” and the social and solidarity economy movement.

The purpose of this workshop was to explore the opportunities for a convergence of efforts between commoners and cooperators, especially in the blending the institutional and financial know-how of co-operatives with the explosive power of digital technologies and open networks. Can we find new ways to blend the innovative, participatory ethic of peer production with the historical experience and wisdom of the cooperative movement? What fruitful convergences between these two forms of social cooperation might we identify and cultivate? What are the possibilities for achieving new forms of “cooperative accumulation,” in which people’s contributions to shared commons would be coupled with value-added services that generate incomes and in-kind provisioning for cooperators/commoners?

A project of open co-operativism would address two important, unresolved issues: 1) the problem of livelihoods in a digital commons economy (how can the economy reproduce itself and inaugurate a different social and economic logic if everyone works without payment?); and 2) the challenge of co-operatives and solidarity economies in leveraging the enormous potential of the new information and communications technologies, and avoiding subordination to the logic and discipline of capital.

“Cooperative accumulation” could occupy a space between commons that have limited or no engagement with markets, and capitalist enterprises that seek to extract private profits and accumulate capital. This intermediary form, open co-operativism, could constitute a new sector in which commoners might pool resources, allocate them fairly and sustainably, and earn livelihoods as members of cooperatives – more or less outside of conventional capitalist markets. What we envisage here is the creation and nurturing of new types of non-capitalist or post-capitalist markets that re-embeds them in social communities and accountability structures.

The key, of course, is how to conceptualize and implement this convergence. As we will see below, a number of promising ideas have been suggested, such as co-operative entrepreneurs co-producing commons; coalitions of ethical entrepreneurs using copyright-based licenses to create zones of production protected from capital and conventional markets; and new models of local, distributed production linked to globally shared knowledge networks. Other ideas remain intriguing but underdeveloped, such as the potential role that co-operative governance might play in commons-based peer production and, conversely, the ways in which self-governance in digital sectors might be applied in the co-operative and social solidarity economy.

Since this report is an account of a workshop dialogue, there are many different perspectives represented, many suggestive but incomplete ideas – and no clear blueprint for how to move forward. It is our hope, however, that this report will stimulate useful inquiry, debate, innovation and a new convergence of movements.

AT THE CROSSROADS: THE CO-OPERATIVE AND COMMONS MOVEMENTS

The global co-operative movement is a significant force for progressive change and yet one seriously challenged by the power of capital, globalized markets, new technological developments, managerialism and social disconnection. Employment in the co-operative movement at 250 million is also larger today than that of multinational companies. In many countries membership in co-operatives (one quarter of all adults in the UK) is double that of trade union membership and far higher than that of mainstream political parties (2% of adults in the UK). Thus the sector could be a key source of countervailing political power. Workshop participants therefore explored whether and how it might be possible to foster a catalytic convergence with the commons movement, particularly in light of the rise of new “collective forms” enabled by the World Wide Web since the mid-1990s.

John Restakis, the former executive director of the BC Co-operative Association in Vancouver, explained that the co-operative movement in many countries is at a crossroads. There is a lack of a powerful common vision for the future, and in many countries this is held in check by a tension and even a polarisation between smaller social solidarity co-operatives and the large, well-established co-operatives in such areas as mainstream banking, insurance and engineering. A number of these co-operatives are themselves under threat by the growing demutualisation of larger co-operatives, a trend epitomized by the takeover of the Co-operative Bank in the UK by external investors, including hedge funds, and the privatisation of large agricultural co-ops like the Saskatchewan Wheat Pool.

On the other hand, there are many important, innovative developments in the co-operative world as well. The success of multi-stakeholder social co-operatives in Italy, especially for social care, has led to the successful international replication of this model. Similarly, solidarity co-operative startups for local services, cafes, sports clubs, local and organic food, fair-trade goods and the urban commons, are expanding in many countries.

There are several key turning point issues faced by the co-operative movement at all levels. Chief among them are how to expand the scale of co-operatives and respond to the corporatisation trend among many larger co-ops. For many co-operatives, this threat is more serious because of a loss of their cultural identities and disconnection from their memberships; a decline in social trust in the co-op organisations, managerial elitism and the gradual but deliberate shedding of any political identity. Ironically, the loss of member trust in the larger co-operatives is precisely the key asset of the new wave solidarity co-operatives, which are aggressively building, not marginalizing, economic democracy and the co-operative ethos and culture. Social and solidarity co-operatives have rediscovered mutual and co-operative systems from the past, and see a progressive and engaged social ethic as an affirmative way to attract to new members.

In a growing number of countries, these co-operatives are developing a plethora of new markets — for community-supported farming, renewable energy, environmental stewardship services, community services, health clinics and pharmacies as well as small business succession strategies that use worker buy-outs and mutuals for the self-employed. All of these co-operative services clearly overlap with the goals and values of the commons movement. Other such initiatives include new digital commons (as discussed below) and urban commons co-ops, such as the co-stewardship of public spaces in Siena and Bologna, Italy, and others nurtured by Labgov, a Naples-based policy laboratory for the governance of commons.[3]

Even with these encouraging developments, the new wave of social solidarity co-operatives face formidable barriers: a lack of access to development capital and training, a significant gap in entrepreneurial and management skills, sectoral and operational isolation in a number of sub-sectors, and a lack of public policy and institutional support from both the state and the larger co-operatives.

The commons movement is also at a difficult crossroads and indeed under assault from many quarters. Public sector assets – forests, water, minerals, highways and other civil infrastructure – are being sold off as tax revenues decline and austerity cuts deepen. In Asia, Africa and Latin America, an unprecedented land grab by hedge funds and sovereign investment funds is appropriating lands that have been managed as commons by indigenous peoples and traditional communities for generations. There is a burgeoning peer to peer co-production sector, but this universe of innovation must generally work within financial and technological systems managed by corporate capital, which means that such commons-based peer production has trouble asserting its sovereignty and independence from capital markets (which explains why car sharing and accommodation sharing is dominated by companies that own the digital platform). The proprietary, capitalist models of collaborative consumption are structured to favour the capital accumulation interests of investors, not the social or equitable interests of users.

The recurrent question posed by these and other examples is: Can we create commons livelihoods without enclosure by the forces of the state or market?

For digital commoners there is a clear need to invent enabling legal structures that can protect their value-creation from predatory capitalism. It is notable that multi-stakeholder and solidarity co-operatives have developed innovative, self-protective solutions in a diversity of service sector markets. What would a shared vision to unite both look like?

As workshop participants grappled with these issues, a number of key questions and concerns emerged as strategically important themes. These included:

- How can we secure a co-operative commons free from capitalist control?

- How can we re-invent economies that remain more locally embedded and distributed?

- How can we forge new working relationships and alliances with “adjacent movements”?

- What can we learn from the history of “co-operative commonwealth” models that deliberately seek to insulate land, people and money from market forces?

- What are the challenges to be addressed in blending open platforms with co-operativism?

- What new vision could unite the commons and the co-operative movements based upon localism, self-determination, social equity and human-centered development?

From this list, what are some of the implications of these developmental opportunities for existing or emerging cooperative structures? First, cooperatives would do well to focus on production that is in line with the values and principles espoused by the sector, serving the common good and not focus exclusively on their own members. Second, while democratic governance is a fundamental principle for co-operatives – operating on a “one member, one vote” rather than the “one-dollar, one-vote” model of investor-owned firms – not all participants in the economic value chain are enfranchised as members. While co-operatives tend to be customer-owned or producer-owned, their democratic reach can be extended by including a wider variety of stakeholders. Cooperatives would do well to integrate the various stakeholders in the governance of their operations, as many “multistakeholder” co-operatives have done. Third, and most importantly, cooperatives may wish to explore new sorts of collaborations with commons, in which they actively co-produce the commons on which they are dependent.

OPEN CO-OPERATIVISM: AN EMERGING VISION WITH GREEN SHOOTS AND COMMONS PRACTICES

The world of the commons is highly diverse so it is difficult to generalize too much about it. But one can safely say that the universe of digital commons is rapidly expanding and flourishing, in part because of the relatively cheap and ubiquitous (or at least growing) access to the Internet in economically developed regions of the world. This has led to new collaborative sectors of production for software, video, music, information, data, scholarly research, among many other intangible resources. A significant report by a major American information technology trade association[4]estimated that one-sixth of US economic activity in 2010 depended upon shared knowledge, code and design – a situation that is likely similar in other “developed economies” as well as the Global South.

While many practitioners in the open and free movements rejoice in the emergence of this collaborative economy, which makes vast amounts of knowledge and culture more accessible for free or at inexpensive rates, the for-profit model is the dominant player shaping the evolution of this sector. Put another way, social cooperation has become a new “input” for capital. Companies are actively investing in collaborative and distributed platforms that foster social cooperation because they know that they can convert social user-value into profitable exchange-value to benefit investors.

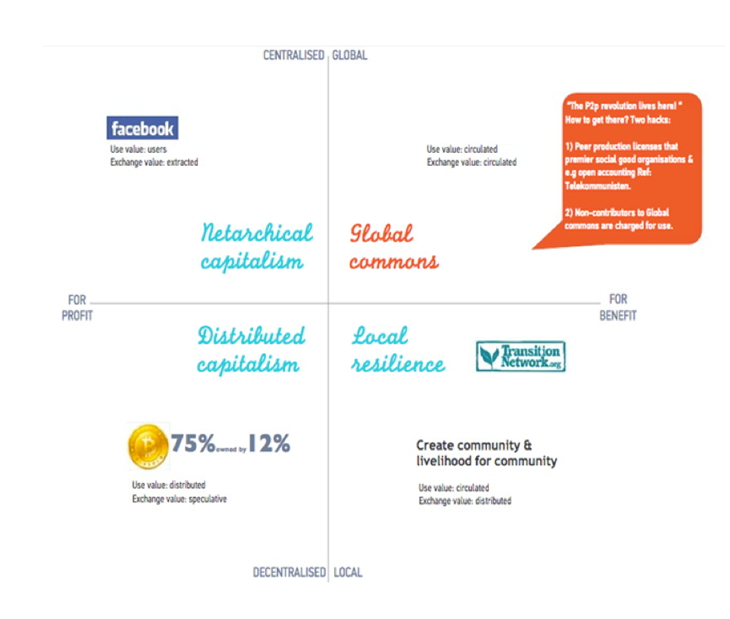

BAUWENS ON NETARCHICAL CAPITALISM VS. GLOBAL COMMONS

Michel Bauwens of the P2P Foundation offered a useful chart (Figure 1 below) illustrating different “value regimes” that new networking technologies have introduced to the knowledge economy, radically changing the terms by which value is created and extracted. Under traditional capitalism, which Bauwens calls “Cognitive Capitalism,” surplus value is extracted from intellectual property that is controlled by big companies and sold for big markups. Only one-fifth of the capitalization of large companies consists of identifiable material assets, and the rest is a matter of some speculation. This means that there is a lot of “missing value” that has intangible dimensions. And a lot of this clearly stems from the social cooperation that is involved in value-creation, said Bauwens.

Open network platforms on the Internet have spawned new ways of generating value, but one of the most powerful is what Bauwens calls “netarchical capitalism.” (See the top-left quadrant in Figure 1 on next page.) Facebook is a prime example. Its massive stock values stem from the user community, whose self-organization and sharing create “attention capital,” which Facebook then sells to the advertising market. “We see an exponential growth of use-value produced by users themselves,” said Bauwens, “but the monetization is only through large, proprietary platforms like Facebook.” This amounts to another form of exploitation of commons. The value of crowdsourcing, for example, has been estimated at $2 per hour, which is far below the minimum wage for conventional work. “People are free to contribute,” said Bauwens, “but there is no democratization of the means of monetization.”

The commons-based alternatives occupy the right side of the chart – Global Commons and Resilience Communities. Resilience communities (bottom-right quadrant) are mostly focused on relocalizing production and nourishing local community, as embodied in the Transition Towns, Degrowth movements and others who see this strategy as ways to deal with the likely disruptions of climate change and Peak Oil. The focus is emphatically on generating community value, and not on political and social mobilizations at larger scales. “A generic critique of this model,” said Bauwens, “is that it does not generate counter-power or a counter-hegemony, as the globalization of capital is not matched or kept in check by a counterforce of the same scale.”

Bauwens believes that the top-right quadrant, the Global Commons approach, offers the best hope for challenging the pathologies of capitalism (in whatever guise) on a transnational global scale. In Global Commons, production is distributed and therefore facilitated at the local level, but the micro-production is networked through global cooperation in the design and improvement of the production apparatus. Even though production may be local, the social, political and economic organisation is global and oriented toward creating a sustainable abundance for all.

Figure 1:

The production alternatives being developed in the Global Commons sector are the ones we should be building, said Bauwens. They represent “a civic P2P economy where value returns to the value creators.” We urgently need to develop new sorts of ethical market entities that can produce “cooperative accumulation” of this sort instead of “capital accumulation.”

DEALING WITH THE PROBLEMS OF NETARCHICAL AND DISTRIBUTED CAPITALISM

So long as netarchical and distributed capitalism have the upper hand, the so-called “sharing economy” will steadily co-opt what might otherwise evolve into commons-based peer production. A relatively small amount of capital will continue to leverage a vast universe of value generated by co-operators on open platforms. One potential consequence of this development – which is already apparent – is a generalized crisis of precariously employed people among large segments of the population (“the precariat”). Since 2008 this precariousness has affected growing segments of both the traditional economy and the information economy workforce.

Contributors to open platforms are generally not socially or economically autonomous, nor can they create livelihoods from their contributions; they must remain dependent on wage labour and its attendant exploitations. At the same time, the new open business models are even more hyper-competitive than the more classic forms of proprietary capitalism; they naturally tend to eclipse the possibility of self-sovereign co-operatives or commons.

Thus we have the spectacle of open platforms re-energizing forms of cooperation, social solidarity and self-provisioning – but on centralized corporate platforms owned by shareholders seeking their own profit. Inevitably, any concern for the common good is subsumed to private interests. Similarly, many cooperatives have adapted to the norms of their competitors in the capitalist economy, seeking profit for their own members and managerial elite, and exploiting the same managerial, financial and economic techniques as their for-profit counterparts. A number of cooperatives have even de-mutualised, in effect aligning themselves with the neoliberal paradigm. Open platforms may well produce the same outcomes over time as for-profit models become the default hosting and investment environments for social co-operation, and aligned with traditional intellectual property rights and control.

Open co-operativism, or more generically, an “open ethical economy,” proposes breaking this insidious pattern by inventing a new sort of co-operative market sector. It would seek an economy where the core actors are co-operative entrepreneurs who co-produce commons and advance their goals through ethical entrepreneurial coalitions or a new type of market sector comprised of collectively oriented enterprises. One tool to advance this vision, for example, is a new set of “commons-based reciprocity licenses” that would enable exchange value to remain more easily within the sphere of the commons and the commoners. Workshop participants identified four other key areas in which social solidarity and commons building could catalyze transformative change:

- The potential of multi-stakeholder cooperatives (or “social and solidarity cooperatives”);

- New strategies for implementing community land trusts, cooperative housing, and mutual currencies;

- New synergies between open network platforms (crowdfunding, crowdsourcing of knowledge, governance through online platforms) and familiar cooperative structures; and

- Collaborative partnerships between city and town governments and citizens — public-social partnerships – to co-develop commons to meet basic needs and to protect common wealth;

To understand the strategic opportunities that these ideas present, it helps to understand the recent history of social change that informs them.

HISTORICAL PRECURSORS TO OPEN CO-OPERATIVISM

The 1990s saw the considerable expansion of a new and growing movement of solidarity co-operatives, particularly in Italy, Japan and Quebec. Historically most co-operatives have been single stakeholder forms of economic democracy based on either consumer, worker or farmer ownership of the means of production, exchange and distribution. While the idea of uniting consumers and producers into a single co-operative was not unheard of, it was extremely rare. In the twenty-first century, however, this traditional dynamic is changing in fascinating ways. Today, for example, as social solidarity economy practices have become the norm in Quebec, most new co-operatives there are being registered as multistakeholder co-ops, said Margie Mendell.

The dynamic innovation of these models began fifty years ago in Asia and Europe. In 1965, a small group of women in Tokyo concerned about pesticides, formed a group of highly innovative food co-operatives, the Seikatsu co-operatives. These ventures went on to pioneer community-supported agriculture and are today the world’s largest co-production and multi-stakeholder co-operative network for locally grown organic food. The Seikatsu movement brings together over 300,000 consumer and farmer members.

In a different sector of the economy, beginning in Brescia in northern Italy in 1963, families of social care service users working alongside carers joined forces to develop collaboratively, solidarity co-operatives. Now known as social co-operatives and operating widely across the economy, these Italian multi-stakeholder co-operatives provide social care, healthcare and educational services. They are also developing new forms of employment for disabled people, those leaving prison and other marginalised groups. Social co-operatives have spread to all regions of Italy and today number more than 14,000. They provide more than 360,000 paid jobs and more than 40,000 job opportunities for volunteers.

Italy’s municipal partnerships with multi-stakeholder co-operatives – boosted by a 1991 law that gave fiscal incentives to them – have helped grow a new sector of the economy that is neither market- nor state-based. An important aspect of this new paradigm collectivises and centralises basic overhead services (administration, personnel, accounting, etc.) to empower smaller social economy ventures. In a sense, it regularises governance for co-stewardship of commons spaces and moves away from rigid bureaucratic methods that increasingly don’t work.

Learning from the Italian social co-operatives, the Seikatsu co-operatives during the 1980s extended their multi-stakeholder system to pioneer the development of social care co-operatives that unite service users and worker owner in the co-design and provision of services. Today Seikatsu co-operatives co-deliver both People care and Earth care stewardship services in ways that provide livelihoods, serve basic social needs, and treat all life as precious commonwealth.

The success of the Italian social co-operatives – accelerated by the 1991 national law – has expanded the movement. Today there are multi-stakeholder co-operative movements in Quebec in Canada and in a wide number of countries in Europe including France, Spain, Poland, Hungary, Finland and Greece. Most recently a new social co-operative sector has begun to emerge in Wales.

The rising levels of government debt and the widespread fiscal crisis of the state in Europe has increased the levels of asset privatisation by the public sector and led to increasing land grabs and especially so in Greece, Spain, Ireland and Portugal. In the UK for example, public assets are being sold to raise revenue and then leased back from the private sector. Meanwhile, unattractive assets with little or negative economic value or great risk are being offered to the local community. Alongside this there is a widespread housing crisis in Europe with spiraling rents and homes in many major cities that are too expensive for ordinary people to buy.[5]

Commons solutions typically provide community stakeholders with practical opportunities for more direct stewardship and governance of land, public assets and other resources important to everyday, non-commercial needs. In her landmark 1990 book Governing the Commons, Elinor Ostrom profiled case after case of resilient commons practices on every continent, from fisheries management in the Philippines to rubber tappers in the Amazon, to Swiss villagers managing their meadows, rivers and Alpine forests since the 13th century, to water stewardship operating over centuries in Spain.

As Ostrom demonstrated, the key difference between an ungoverned “common-pool resource” and a resilient commons is community stewardship that co-manages the resource with ethical rules to weed out free riders, shirkers and vandals.[6] As described in several recent books, [7] there is evidence of an emerging new economy of the commons that ranges from open source software (Linux, LibreOffice and thousands of other programs) to seed sharing commons in India; from the Peruvian Potato Park protecting 500 species of genetically valuable potatoes to the CouchSurfing “gift economy” of free hospitality for some five million travellers in 97,000 cities and towns globally. Such examples demonstrate that, whether in natural resource or digital contexts, principles of commons-based governance can function successfully.[8]

NEW SYNERGIES BETWEEN CO-OPERATIVE COMMONWEALTH MODELS AND DIGITAL COMMONERS?

Now that the commons movement and peer production sectors are starting to move beyond virtual spaces to take on actual physical production and to organize new models of social behavior (“commoning”), it is easier to see that the mental prejudice of segregating virtual, digital production from more conventional production, markets and social organization is misguided. The two realms are blurring, and that argues for a more candid assessment of the potential synergies between the two realms. Digital commoners would do well to contemplate the lessons of the co-operative commonwealth experience, and the co-operative and solidarity economy ought to consider how digital networks, information and communications play a role in value-creation, especially in a social context. Perhaps “social information” constitutes a fourth form of “fictional capital” to be added to Polanyi’s triad of land, labour and capital. And perhaps there is even a fifth element, the idea of Buen Vivir, “good living,” and social relations – also critical elements of value-creation that capital is seeking to commodify.

Three fields of action in the co-operative commonwealth world merit special attention and study: the community land trust movement; the efforts by the co-operative and solidarity economy movements to address precarity, such as the Chantier movement in Quebec; and financial models based on mutual credit and co-operative currencies. Although the ties between these efforts and digital commons are not well developed, one can easily imagine digital platforms helping to coordinate and expand participation in such projects. One can also envision digital networks enhancing social impact, political organization and effective management in these areas.

THE COMMUNITY LAND TRUST MOVEMENT

Like the multi-stakeholder co-ops and new digital commons, the community land trust movement – working in the rich tradition of co-operative commonwealth practices – has many lessons to offer those new to the economics of the commons. The movement’s most important lessons involve how one can learn to put key commons ideas and principles into successful practice.

Land values typically account for 25% to 75% of house prices, so if you can remove land from the market and make it available through other means, you can both drastically reduce housing prices and keep homes permanently affordable. That is what community land trusts (CLTs) do. The diagram below shows how community land trusts maintain affordable housing in perpetuity by removing land from the market and placing it under democratic ownership and control. The land is managed through a trust governed by civil society stakeholders.

In his last book, Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community, Dr. Martin Luther King proposed in 1967 a set of co-operative solutions based upon social economic trusteeship of land and other assets. To pursue this strategy after Dr. King died, Bob Swann and Slater King (the cousin of Dr. King) established one of the first US CLTs, New Communities Inc., in 1969, on 5,000 acres of land in Leesburg, Georgia. Development of the CLT proceeded slowly, however, until innovation in New England showed the way.

A CLT in Burlington, Vermont, led by then-Mayor Bernie Sanders was the pioneer. Now known as the Champlain Housing Trust Vermont, it was founded as Burlington Community Land Trust in 1984 after cutbacks in federal programs to fund affordable housing. Instead of pursuing the conventional strategy of using only housing development subsidies, which would try (and ultimately fail) to keep up with rising land values, the CLT works by taking land out of the market and keeping it in trust.[9] Crucial for its success was a social-public partnership that was struck between community groups and the city council. To set up the CLT, the city supplied a core revenue grant and an additional $1 million line of credit from the city employees’ pension fund.

The CLT has expanded steadily and now manages over 2,000 affordable units of housing, including part-equity homeownership and rental apartments. The CLT also supports on its land an additional 81 limited-equity homes provided by five housing co-operatives. Besides housing, the CLT has co-developed a day centre for the elderly; a nursery facility; managed office space for social enterprises and non-profits; a storefront for the region’s community development credit union; and a multi-unit housing and workspace complex for local businesses.

Since 2000, municipally supported partnerships are responsible for the most innovative CLT work in the United States, leading to a new City-CLT partnership model. A growing number of cities including Chicago, Albuquerque, Irvine (California), Portland (Oregon) and Syracuse (New York) are supporting existing CLTs, starting new ones and actively fostering their development. The Irvine master plan is building 5,000 “permanently affordable” homes on a redundant military base of 4,700 acres.

This new-found support stems from the proven ability of CLTs to use discounted land and other government subsidies to maintain the affordability of housing despite rising real estate markets. For 30 years neither land nor homes have been lost from the CLT portfolio in Burlington. CLTs also have a track record for avoiding debt and mortgage foreclosures when markets contract. Thus CLTs are powerful vehicles for providing stewardship of both land and housing, especially when working hand in glove with city staff and backed by local politicians.

City-CLT partnerships are winning wider recognition as a robust way to prevent the loss of affordable housing (and other community assets) by using municipal and community development investment to secure the resources. There are now over 250 CLTs in the USA and about 50 established with more than 100 in the pipeline in the UK. The model is being developed in Canada and in Belgium, and interest is gaining in France and Portugal. CLTs are attractive because they are flexible models for a wide variety of urban commons development; they have been applied not just to housing but to workspace development, sites for community-owned energy generation, and to new forms of urban agriculture and community gardens.

New forms of community ownership (charitable trusts, charitable companies, community interest companies, community benefit societies) have flourished in the UK in recent years in response to austerity cuts that have closed libraries, hospitals and other public facilities and to the closure of locally owned businesses following the construction of shopping centres on the edge of towns. Grassroots groups are increasingly raising community investment funds through shares issued to the public; the investments are being used to save local pubs from closing and to fund community-owned renewable energy. A number of local football clubs have even been revived through successful community ownership campaigns. Such successes are fueling larger ambitions. For example, 3,500 community investors have mobilised local capital to rebuild the Hastings Pier in East Sussex, England, after a fire that threatened it with demolition. A co-operative association has been developed in Dover, England, to utilise a CLT for the community buy-out of one of the biggest ferry ports in Europe. Growing community and co-operative share issues and best practices are collaboratively supported by Co-operatives UK, Locality and the Plunkett Foundation. This success resonates with the urban commons movement growing in Italy from Naples to Rome to Bologna. The UK best practice model for community shares has been replicated in western Canada, in Alberta, through a growing Unleashing Local Capital movement.

The grassroots struggles in the 1990s to carry out successful community buyouts of many rural islands in the Hebrides inspired the development of CLTs across the UK. Starting with Scotland, UK legislation has given communities the right to buy or take over essential community resources – an advance that has proven less effective than it might be because it is not feasible for communities to exercise many of the rights. But against the odds, community-led solutions have developed some key precedents and can be improved upon through commons strategies and open forms of co-operativism. Ways and means of rescuing and transforming public libraries, for example, could offer strategic pathways to develop digital assets and to assist “knowledge and know-how commons” to emerge and further diverse other forms of commoning. Open co-operativism offers scope for groups to learn about best practices emerging in a number of countries on how to develop commons-based solutions using co-operative tools..

While larger CLTs are beginning to emerge, Letchworth Garden City is a key precedent. The city was established in 1903 when over 5,000 acres of land north of London were acquired over 50 years the city at farmland prices. The entire city is built on land co-operatively owned by the city residents. All the utilities were municipally owned until 1945, and this income and the economic rents paid by the businesses in the town made Letchworth economically resilient. While the utilities and much of housing was demutualised after 1979, the Letchworth City Heritage Foundation continues to own most of the commercial land in the city and uses the profit on this portfolio to continue to reinvest for the common good and to fund community services.

In other countries where municipal utilities were not privatized as in the UK, co-operative and municipal partnerships have played a lead role in developing green economy solutions. In Denmark, co-operative wind energy developers have creatively partnered with local towns and cities to decentralise energy services and co-develop green micro-grids. Copenhagen’s energy system is co-managed by a municipal energy company and 21 district energy co-operatives. Berlin has recently voted to re-communalise the energy grid for the city. Across Germany green energy solutions are increasingly driven by almost 1,000 energy co-operatives that are introducing renewable energy technologies. Social finance is typically provided by a combination of finance packages from municipal savings banks, regional co-operative banks and KfW, a unique public development bank providing “cheap money” to support green energy solutions.

CO-OPERATIVE COMMONWEALTH STRATEGIES TO ADDRESS PRECARITY

From Greece to Spain and right across Europe and many other developed economies, austerity combined with the costs of an aging population is on the one hand destroying the welfare state, and on the other hand, it is leading to widespread and insecure forms of employment as public sector work opportunities contract. The precariat, once on the margins in many countries, has since 2008 moved to the centre stage of twenty-first century forms of work as people struggle to survive. In the UK since 2010, four in ten new jobs are being created by self-employed people. The vast majority of these new jobs are at poverty levels in terms of income. While some former public sector workers have launched new business enterprises, commercial startups without democratic and co-operative legal structures, and based on traditional capitalist and venture capital models, are leaving the majority of risk-takers behind, with little to show for their sweat equity.

Margie Mendell told of the building of an alternative base/coalition in Quebec, the Chantier de l’economie sociale, and how that started to leverage public policy shifts in Quebec, which in turn changed the discourse of Quebecois politics. It re-introduced the social sector into discussions that were previously seen as matters for the market and state alone; it demonstrated that collective enterprise in all sectors could be efficient and “profitable” while meeting social and environmental goals and contributing to overall well-being: in essence, reconciling the social with the economic. Beginning with work in the 1980s in southwest Montreal, the Chantier is today a vibrant “network of networks” for social solidarity work, co-operatives and new forms of innovation. They were the instigators of the solidarity co-operatives for jobs from 1997, an achievement that stemmed from creating the first Canadian employment partnership to unite the public, private, trade union and social economy sectors under one alliance.

The Chantier movement is a “network of networks” that includes producers of both goods and services, social movements such as labour and environmentalists, and development intermediaries. As such, the Chantier movement has been able to leverage capital in the form of labour solidarity pension funds and private and public capital. Social enterprise solutions have been applied to housing, child care, prenatal care, home care, worker training, community broadcasting and recycling, to name a few. New sectors – ICT, social and eco-tourism, and culture – are also part of the social economy in Quebec.

The recurring theme in each sector has been finding and developing avenues of social solidarity. This means getting beyond project-based campaigns and developing a more holistic, integrated perspective. The Chantier-like systemic approach, which initially served as a response to de-industrialisation, is increasingly responding to social aspirations and unmet needs, attracting young people committed to an economy built on solidarity.

Yet again in Quebec, we can see the critical importance of strategic public-social partnerships. The economic activity generated by the Social Solidarity Economy in Quebec now accounts for 8-10% of GDP, includes 8,000 social enterprises and co-operatives, and provides 250,000 jobs. The success of the Chantier movement in one province in Canada has remarkable similarities to that of the more widely reported co-operative economy miracle of Emilia-Romagna, the region of northern Italy that includes Bologna. The presence of 13,000 co-operatives in just one province represents the greatest regional density of co-operatives in Europe if not the world. Even though the FabLabs of today’s digital economy stem directly from academia and in particular M.I.T., they can trace their conceptual roots to the governance and organizational innovations of co-operatives started in both Montreal and Bologna decades ago. The success of Social Solidarity Economy methods has recently been recognised by a UN report published by UNRISD. The report brings together the findings of 70 research papers and also documents the key role of the state in co-constructing public policy with social economy actors including co-operatives, social enterprises and trade unions.[10]

There is a considerable body of work available that documents effective ways for organising the precariat through co-operative and social solidarity economy systems. In some countries like the Netherlands, trade unions are supporting these innovations and developing either general or specialist sector trade unions for freelancers and sole traders. Since so many of the unemployed are former trade union members from both the public and private sectors, there is wide scope to encourage more trade unions to do the same. Co-operatives UK is about to begin a project to assess how mutual and trade union solutions for the self-employed might be combined and integrated.

Kevin Flanagan of the P2P Foundation suggested that special attention be paid to helping the precariat obtain access to affordable workspace, housing, financial services and co-operative capital – something that the Edgeryders network has dubbed #hackcare.[11] It would be especially helpful to provide assistance in commons-based ways – through sharing know-how and supportive tools, for example. However, the precariat tend not to have experience in starting up and managing successful business enterprises let alone co-operative ones, so this poses a challenge.

The experiences of the Chantier movement, the Italian co-operative movement and the community land trusts all speak to these challenges. In light of similar efforts in Greece to develop commons-based peer production solutions in the face of state austerity, there is considerable scope to develop innovative co-operative and commons solutions. Similarly, the resourceful innovations of Cooperativa Integral Catalana (CIC) in Catalunya also point to the rich diversity of commons and co-operative solutions that could be emulated. Sofia Cardona observed that “always the problem comes back to money.” Kate Swade of Shared Assets replied that “money can be different. Financial systems are not like the weather; we can reconstruct the money system. This is such a big idea!”

REVIVING CO-OPERATIVE CAPITAL AND MUTUAL CREDIT

Pat Conaty stressed that it is important to recover financial models based on mutual credit and co-operative currencies. These were pioneered by the first wave of co-operative movement activists. These included the early mutual building societies in Great Britain; Josiah Warren’s co-operative stores in the 1830s; and Proudhon’s “people’s bank,” an unsuccessful venture to replace the private Bank of France in 1848 but whose mutual banking ideas influenced the public banking proposals of American Populists in the 1890s and thereafter the development of public banking after World War I.

Early mutual lending was interest-free. For example, peer-to-peer interest-free lending for house-building was once the norm in Great Britain. Indeed, it operated for over a century from 1775 when the first terminating building society was established in Birmingham. By the 1870s there were over 900 such interest-free lenders trading; almost every town had one. The similar Starr-Bowkett societies were also popular interest-free loan organisations, operating widely in England from the 1840s until the 1890s. Most of these practices have been forgotten but they have left in their wake today a number of successful co-operative models operating below the radar screen.[12]

New startups offering interest-free lending were banned at the beginning of the twentieth century in the UK, but many of the older enterprises still exist elsewhere internationally. These include the successful interest-free JAK co-operative banks in Sweden and Denmark, and CoopHab in Brazil that makes interest-free mortgages for a diverse range of co-operative housing. The Fund for Humanity, the community lending affiliate of Habitat for Humanity, has financed over 500,000 homes by providing interest-free loans to community self-build housing groups since the 1970s. The development of JAK banking in the 1930s inspired the development of the WIR co-operative currency in Switzerland. This is the largest mutual lending system globally, with over 65,000 members and participation by one in four Swiss businesses.

Inspired in part by these co-operative precedents, there is now an unprecedented amount of experimentation and innovation in launching new types of complementary and digital currencies. The rise of Bitcoin is particularly notable as a digital technology because its “block-chain ledger” software is a distributed, peer-to-peer system for assuring the integrity of the currency, without the involvement of government or banks. Its open source protocols are widely available, which has helped build confidence in the security and performance of the system. Legitimate concerns have been raised about the financial speculation, libertarian ethos and ecologically wasteful use of electricity associated with Bitcoin. But that does not diminish the fact that the block-chain ledger technology that lies at the heart of Bitcoin is a fundamental cryptographic breakthrough that proves that it is possible for strangers to exchange money or assets with no preexisting trust.[13] Thus, apart from the fate of Bitcoin, this software innovation opens up new possibilities for online collaboration without the necessity of third-party guarantors such as traditional banks and government bodies.

This has obvious implications for co-operatives and commons that wish to capture and protect the surplus value that their co-operators/commoners create. A new digital currency can now feasibly become the vehicle for a self-organized community to measure and exchange value among its members. It need not even run afoul of national currency laws protecting fiat currencies to the extent that the digital currency represents a form of “digital asset exchange” protected by contract law.

One of the more ambitious experiments to build a co-operative currency is FairCoin, which was launched in October 2014 by Fair.Coop, a project associated with CIC in Catalunya. FairCoin has been designed to adapt the block-chain technology of Bitcoin with a more socially constructive design. (Faircoin relies less on “mining” new coins than on “minting” them in a more ecologically responsible, equitable ways.) CIC correctly recognizes that the existing monetary system and private banks pose insuperable barriers to reducing inequality and ensuring productive work and wealth for all. The only “realistic” alternative to existing fiat currencies and foreign exchange is to invent a new monetary system. An open letter from the Fair.Coop Team recently explained:

We need to create a new, decentralized economic system: a metasystem to support, feed and connect multiple autonomous systems built in a distributed manner. Foreign exchange markets trading cryptocurrencies have been expanding rapidly in the past two years. With the concept of Global South, communities can define themselves and support one another from remote corners of the world. It’s time for the networked global citizenship to empower themselves as part of a fair economic system, without intermediaries, and create the change that has not been achieved from above.

Sofia Cardona, an activist with CIC explained that organisations have “made history by co-operating; that is why it is so important to do so. Now with the Internet it is possible to make history faster.”

It is of course to early to know if FairCoin will succeed or encounter insuperable difficulties. But the rationale for attempting to devise such currencies is compelling, especially now that new developments in peer-to-peer computing make such innovations entirely feasible. The benefits for the commons and co-operative worlds could be enormous by enabling interest-free lending and independence from conventional finance.

It bears noting that the block-chain ledger technology has important uses beyond alternative currencies. The technology is quite revolutionary because it enables trusted peer-to-peer exchange without third-party guarantors such as government or banks.[14] The block-chain technology could therefore be used to help many new types of commons to emerge. For example, homeowners with solar energy systems could generate electricity and mutually share it as a “solar commons” using a regional smart grid and the Bitcoin-like transactions to keep track of people’s production and usage of electricity.[15] This theater of change has great strategic potential for spawning radically new types of commons-based production and governance – which the co-operative movement should be in the forefront of embracing.

Margrit Kennedy, the late expert on alternative currencies, has said that an average of 48% of the cost of any product is debt. That’s why “open products” developed through collaboration on open platforms is so attractive, said Michel Bauwens: they can achieve the same or better results as conventional products for one eighth of the cost. This not only makes peer production highly competitive but more socially attractive than conventional production methods. Unfortunately, peer production usually does not have access to the same sorts of finance and capital that conventional proprietary, capitalist businesses do.

This makes it all the more imperative that traditional co-operative management explore the opportunities available through digital currencies. It should also explore better ways to leverage the power of digital and open manufacturing methods; otherwise, capital will inevitably exploit all the advantages of open platforms, leaving commoners with little to show for their participation. For Annemarie Naylor, Director of Common Futures in the UK, the three most important strategic needs with respect to finance is to reinvent it in three fundamental ways – in providing great access to liquidity, in risk-pooling and on raising capital for patient investment.

Could a convergence between co-operativism and the “open economy” lead to a super-charged cooperative sector that could generate a new type of post-capitalist and ethical marketplace? That is the clear implication of the many precedents and innovations that we cite here. There is great promise to be found in expanding and developing multistakeholder (solidarity) co-operatives, community land trusts, public banks, public-social partnerships, co-operative commonwealth strategies, open network platforms for commons-based peer production, new systems of finance and alternative currencies.

There is a compelling strategic need to explore practical strategies, models and collaborations, both within and between the commons and cooperative movements. While the philosophical and historical are important elements of this discussion, so are the political, pragmatic and situational steps for moving forward. The best practices and guiding principles of the social solidarity economy offer a solid foundation from which to build a rich and flourishing new open co-operativism sector.

MAKING IT HAPPEN

Based on two days of discussing the historical inspirations and contemporary opportunities for open co-operativism, participants concluded the workshop by recommending an agenda of goals and suggesting possible means to achieve them. The primary goal is to build a larger movement based on the principles of open co-operativism, which, stated simply, is a movement that can embrace the history, institutional innovations and finance models of co-operatives and blend them with the power of open networks, open source ethic, co-operative principles and commitment to the common good.

Participants identified three general priorities for helping actualize a new vision of open co-operativism. These include: 1) New regimes of law, governance and management; 2) New and better systems to aggregate patient capital for “co-operative accumulation”; and 3) Blending co-operatives and digital/open platforms.

MOVEMENT-BUILDING STRATEGIES

Building a new movement based on open co-operativism requires finding ways to build bridges between the co-operative movement and commons sectors. Participants suggested a number of conceptual approaches that would be helpful:

- Build awareness and a shared discourse

- Develop a statement of guiding principles

- Initiate new dialogues and develop a shared roadmap for collaboration

- Start new commons as co-ops

- Identify cooperative solutions for the precariat including unions and mutuals for the self-employed that secure “economies of co-operation”

- Expand stewardship of the commons through “co-ops for the commons”

- Identify common-denominator solutions through “commons for co-ops,” and

- Treat land as a common platform for co-operative cities and “adventure capital” as a tool to develop convivial finance solutions.

Participants also identified a number of organizational strategies that could be pursued:

- Convene movement-building events such as conferences, symposia and workshops

- Host festivals to reach out to new partners and the general public

- Start a standing forum to host creative dialogue on Open Co-operativism

- Develop an action research programme on key questions

- Collaborate on a co-operative toolkit for developers

- Start working task forces issue of joint concern

- Adopt “resist and build” strategies (e.g., La Via Campesina)

- Cultivate the cooperative ethos because culture matters as much as legal forms

In an attempt to summarize the general challenge facing both the co-operative and commons movements in embracing the vision of open co-operativism, David Bollier suggested that co-operatives need to understand the importance of adopting new digital forms of organization and practice inspired by historical examples, and commoners need to develop new institutional, legal and financial structures that can protect their resources and communities, and to build richer alliances with other movements. These general shifts and reorientations are needed in order to build new forms of political power and to build new self-reliant production and livelihood systems that can to address precarity with genuine solutions and get beyond the Market/State duopoly’s control of the polity. Ultimately, the new organizational forms and an open, co-operative ethos can generate value in decentralized, transparent ways, and provide real democratic empowerment independent of the state.

But the vision of open co-operativism must work on many levels in a coordinated fashion, warned John Restakis: “There may be a convergence of commons and co-operatives, but even with digital currencies and the co-operatizing of resources, does it alter the configurations of power and the cultural paradigm? If there is going to be a particular type of political movement, then we will need specific models and legal structures to develop it. We will need to identify and promote examples, and identify institutional supporters and allies.”

Janis Loschmann, a graduate student who is studying the commons at the University of East Anglia, suggested that a key area of collaboration between the co-operative and commons movements could be “a joint resistance to the monetisation and exploitation of knowledge, work and nature. What is crucial to assert is the value of work as reproductive,” by which he meant “the whole value of work, both useful non-market work and some of what we know as market work. Commons value recognises the higher importance of use-values.”

THREE GENERAL PRIORITIES FOR OPEN CO-OPERATIVISM

BUILD AND EXPAND NEW REGIMES OF LAW, GOVERNANCE AND MANAGEMENT

The idea of open-cooperativism implies some significant shifts in how we conceptualise use-value and exchange-value, and also in crafting the legal, organizational and social structures for capturing that value for co-operators. Fortunately, there is a rich history in the co-operative movement that offers useful guidance in meeting this challenge. But the “old solutions” need to be rediscovered and in many instances adapted for digital environments in order to make them work today. Conversely, many segments of the commons and “sharing economy” world need to learn about past solutions that could address vexing contemporary challenges and help overcome predatory capitalist dynamics.

Participants mentioned many specific strategies for improving law, governance and management:

Policy regimes to support open co-operativism. Typically the state lends its legal support and resources to advance the capitalist market sector – private investors, corporations, markets – but there is an important role for the state to play in supporting both co-operative and digital commons models. Many of these policy regimes have to do with finance and capital, as described below, and with the sanctioning of organisational forms such as co-operatives, garden cities, public banks, land trusts, and other forms of mutualisation.

Heike Löschmann of the Heinrich Böll Foundation agreed that the idea of “a partner state” could help: “Land grabs are increasing across both Africa and in Europe. We need to find ways to remove land, people and money from the market. We cannot do this without the development of public-social or public-commons partnerships.” This would be entirely consistent with Article 14 of the German constitution, which asserts that private property has two social obligations – that it should not compromise the public good and that it should serve the common good. Law and public-social partnerships could be one important way to counter extractive private property, she said.

A timely test case for the idea of the partner state is whether it will adopt public policies to support open networks. While policies to support “net neutrality” remain hotly contested, there are others that are also needed, such as open access publishing policies for government-funded scientific research;[16] laws to enable municipal wifi and mesh-networks;[17] and “open data” regimes and resources that would allow local governments and others to analyze Big Data from public sources to devise useful social policies and programs.[18]

One of the most ambitious, comprehensive set of public policies to support commons-based peer production was developed in 2014 by the FLOK Society in Ecuador (FLOK stands for “Free Libre Open Knowledge”). Although the set of recommendations has not been enacted into law in Ecuador, The Commons Transition Plan produced by the year-long research effort is designed to enable every sector of Ecuador to be organized into open knowledge commons, to the maximum degree possible.[19]Ecuador initiated the FLOK project as a way to go beyond neoliberal economics and policy, particularly archaic intellectual property regimes that ignore network dynamics and prey upon the value created by nonmarket communities. The Commons Transition Plan is a comprehensive, sophisticated and integrated synthesis for moving to the next stage of commoning and peer production on open networks.

While policies to foster commons-based peer production remain rudimentary and scorned by most national governments (which tend to be dominated by vested corporate interests), there are important if fragmented initiatives that could take these views to the next level. The co-operatives known as CIC, in Catalunya, for example, are actively reviewing the Commons Transition Plan as a template for their own policy advocacy. In Greece, workshop participant John Restakis recently helped George Papanikaloau of the P2P Foundation develop a policy agenda to promote commons-based peer production, mutualisation and co-operatives in that country. The agenda is intended to guide the political coalition Syriza if it is elected in 2015.

Create enabling legal structures and models of good practice. Sometimes private contract law can be very useful in achieving new legal structures for co-operative behaviors; two prime examples are the Creative Commons licenses and the General Public License for software. But since those licenses do not necessarily protect the surplus value created by an online commons – large corporations often appropriate information on open platforms or in the public domain – a new type of “commons-based reciprocity license” may be needed. Michel Bauwens of the P2P Foundation and his colleagues are developing such a license right now in order to let commons protect their self-generated value (knowledge, code, images, music, video).[20]

Of course, the state has a very important role to play in using policy to legally sanction certain types of co-operative organization and behavior. For example, it could more aggressively authorize new sorts of social organizations/commons, such as the multi-stakeholder co-operatives seen in northern Italy and in Quebec, or in the municipal government partnerships with social commons in a number of Italian cities. The state can also use tax money to incentivize businesses to adopt more co-operative forms and practices, and to develop infrastructure that can benefit co-operatives and commons (e.g., municipal wifi systems).

Commons/solidarity economy startups. There was agreement that support and attention is needed to help start new commons and solidarity economy enterprises. These include cafes, food services, social services, organic agriculture, urban commons (e.g., Bologna, Siena, Quito), digital commons, finance institutions for cooperative capital, and “solidarity services” (e.g., informal, DIY services such as pharmacies, food and healthcare to help people in extreme need, such as the Greek victims of austerity politics).

There was also agreement on the need to build integrated ecosystems for the new organizational forms, particularly in urban environments. Co-operatives could learn from the ecosystems for business startups, said Pat Conaty. Instructive examples of building an ecosystem of co-operative capital can be seen in the work of the JAK Bank in Sweden; Coop Hab in Brazil; the Fund for Humanity, a Bay Area nonprofit that provides interest-free loans; the Evergreen Co-operatives in Cleveland; and the National CLT Fund (UK), which uses finance to facilitate each stage of developing community land trusts. Michel Bauwens suggested that it would be helpful to develop a map of what elements of such a co-operative ecosystem are missing in a given region, and then to develop meta-level map that would integrate the various elements.

Public/social partnerships. As described above, the multi-stakeholder co-operatives in Italy, Quebec and Japan are showing that government with a small “g” can work, especially at the local level. These forms are a way not only to meet people’s everyday needs, but a way to reinvent the very idea of government and to allow people to say, correctly, “We are the government.”

This is obviously a more problematic challenge in countries where government is not a friend and supporter of delegations of authority to commoners. A key issue is how to structure the relationship of social commons to the state, and how to federate them financially and operationally so that they can scale. Such efforts can work, and when they do, they can dramatically alter the political culture.

AGGREGATE PATIENT CAPITAL (AKA “CO-OPERATIVE ACCUMULATION”)

In discussing the need for “co-operative accumulation,” workshop participants identified several general goals that should be pursued:

- Communities must devise ways to retain the surplus value that they create;

- Practical models for make labor inalienable must be imagined and built;

- Commons can be used to reduce risk and the need for capital;

- We must develop new ways to scale access to capital (risk, working and investment capital), such as public banks and sources of “adventure” capital.

Participants suggested a number of specific means for achieving these goals:

- Open tech assessment to create reliable criteria for investment;

- Models based on CASX (Cooperativa d’Autofinançament Social en Xarxa), a Brazilian project to start up a self-managed, assemblearian, financial cooperative;

- Startup funding and support;

- The creation of hybrid legal forms for investment (e.g., high risk and low profit);

- Peer-to-peer knowledge transfer systems for enterprises of diverse sizes and trade sectors to secure radical levels of carbon reduction like the Climate Smart network in British Colombia;

- Zero-cost risk capital via advance sales; and

- Conduct research into new possibilities.

The general challenge in aggregating capital to serve open co-operativism is: How to invent and develop low-cost finance at different levels? The provisioning of inexpensive capital is critical to the success of such projects, whether they be community land trusts, mutualized services, multi-stakeholder co-ops or peer production projects for open design and production. But the creative expansion of finance for open co-operativism is a complicated issue because political bodies must often adopt new policies for ownership, finance and organizational forms. Also, sometimes cultural traditions are an impediment; countries with weak bonds of social trust and local initiative often find it more difficult to pursue these options. Perhaps the burgeoning field of social finance will be able to expand access to patient capital for collective enterprises.

BLENDING CO-OPERATIVES AND DIGITAL/OPEN PLATFORMS

Co-operatives must begin to leverage the power of “sharing platforms” on the Internet and other open platforms. As the discussion above suggests, there are many opportunities for co-operatives – and a great need to educate digital commoners about the value of co-operative organizational, legal and finance models.

The Catalunyan group CIC is at the forefront of many such explorations, most notably its FairCoin currency to enable co-operatives worldwide to share value. Its Guifi.net mesh networks, facilitating low-cost access to wifi, is another fascinating innovation. The block-chain ledger technology, as explained above, offers important new opportunities for using open networks to build new types of co-operative production and sharing.

As Benjamin Tincq of Ouishare noted, sharing platforms give users greater control than traditional institutions while providing more directly responsive governance. By comparison, he noted, traditional co-op models seem cumbersome and expensive. By embracing open platforms, it may turn out that co-operatives can become both more competitive in a market sense as well as more democratic and public-spirited in a cultural and organizational sense. Tincq noted that there are a number of hybrid organizations that consist of co-operative or commons-based social practices “with companies wrapped around them.” He cited the organizations Inspire, Loomio, and Liquid O. The point is that the enterprises may legally and fiscally operate as businesses, but in practice they function as co-operatives and commons.

CONCLUSION

Our current moment in history may be rife with serious economic and political challenges, but it is also rich with opportunities. There are many more ways than we may realize to develop innovations to meet basic needs in socially just and ecologically responsible ways. Remarkably, mainstream politics and economics barely talk about such goals, let alone explore feasible models for achieving them. This workshop was an attempt to bring such ideas to the fore.

There is a rich history of the co-operative movement that can guide and instruct contemporary movements seeking to invent new models. For its part, the commons movement and many associated movements – the Social and Solidarity Economy, Transition Towns, peer production, food relocalization, and community land trusts, among others – are already pioneering fascinating new projects and public policies. A convergence of these movements with the experience and ideals of the co-operative movement could be formidable indeed.

International organisations that are focusing on removing land, labour and capital from the market can offer strategic guidance in developing a commons mission for the twenty-first century. Here the Chantier movement in Quebec, the social co-operative movement in Italy, the Seikatsu movement in Japan and the growing Community Land Trust movements, offer practical lessons about what is to be done. No movement is focusing on all three objectives yet, but they each contribute to developing a commons agenda by focusing on sharing know-how, decommodifying land, radically integrating co-operative systems, and making capital a servant to social needs.

One of the most fruitful arenas for exploring new synergies and collaborations is surely the digital realm. The power of open source principles, now proven beyond a doubt, is rapidly proliferating into many other areas of culture, production and social life. The prospect of more participatory, socially convivial forms of production – accountable to communities and mindful of the larger common good – has never seemed more achievable. Still, there are important organizational, legal and financial hurdles to overcome – not to mention cultural and political differences – that must be dealt with if co-operatives are to find common ground with digital commoners and peer producers. Fortunately, there are emerging models such as multi-stakeholder cooperatives that could be vehicles for such cooperation.

Moving towards such a future will require significant amounts of research, dialogue, improvisation, venturesome initiatives and simple courage. We hope that this account of the Open Co-operativism workshop will provide useful inspiration and guidance for further explorations of the possibilities.

APPENDIX: WORKSHOP PARTICIPANTS

Michel Bauwens Thailand P2P Foundation / Commons Strategies Group

David Bollier US Commons Strategies Group

Pat Conaty UK Co-operatives UK / New Economics Foundation

Sofia Cardona Spain Cooperativa Integral Catalana

Kevin Flanagan Ireland P2P Foundation

Mike Lewis Canada Canadian Centre for Community Renewal

Heike Löschmann Germany Heinrich Böll Foundation

Janis Loschmann Germany/UK University of East Anglia

Margie Mendell Canada Karl Polanyi Institute, Quebec

Annemarie Naylor UK Common Futures

John Restakis Canada British Colombia Co-operative Assn./FLOK project

Kate Swade UK Shared Assets

Benjamin Tincq France Ouishare

TOWARD AN OPEN CO-OPERATIVISM: A New Social Economy Based on Open Platforms, Co-operative Models and the Commons

- A Report on a Commons Strategies Group Workshop

- Berlin, Germany August 27-28, 2014

- By Pat Conaty and David Bollier[1]

- Supported by the Heinrich Böll Foundation with assistance from the Charles Léopold Mayer Foundation

REFERENCES

[1] Pat Conaty is a Fellow of the New Economics Foundation and a Research Associate of Co-operatives UK. David Bollier is Cofounder of the Commons Strategies Group and an independent author, blogger and activist whose focus is the commons as a paradigm of economics, politics and culture. This report is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike (BY-SA) 3.0 license.

[2] Dave Grace and Associates, for the United Nation’s Secretariat Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Division for Social Policy and Development, “Measuring the Size and Scope of the Cooperative Economy: Results of the 2014 Global Census on Co-operatives,” 2014, available at

http://www.davegraceassociates.com/uploads/Global_Census_on_Cooperatives_-_Summary_Analysis.pdf

[3] http://www.labgov.it